TEMPLE OF ARTEMIS 2018-2020

Participatory Brand Development

Participatory Brand Development

by Anna Paterlini

Despite global economic problems, geopolitical conflicts, and a global pandemic, the travel industry is a market that is still growing globally and, in some countries, is also one of the main sources of national GDP. Places are today, more than ever, in competition with each other and all equally eager to sustain competitive advantages in an ever-changing market as well as ensure their survival as tourist destinations while fostering sustainable development.

Traditionally this task has always been the realm of place marketing. However, a new approach has recently been gaining traction: participatory place branding. Based on the assumption that a place narrative created in partnership with the local community is more appealing and ethical than one that is created from the top down, participatory place branding was defined by Aitken and Campelo (2001) as the ‘holy grail of destination branding’.

This research aims at contributing to this debate by starting a process of re-branding the archaeological site of Jerash, beginning with the history of its own community and the aspects and stories that really make it unique.

Through the study of the tourist base that visits Jerash, and the involvement and contributions of the local community, the project works to make a substantial addition to the sustainable management of the archaeological site of Jerash. Through a detailed qualitative survey of community perceptions and experiences of Jerash over time and up to the present day, this research aims to provide a synthesis of the historical and contemporary significance of the site for its community, attempting to demonstrate the potential of inclusion of local narratives in place branding processes and, eventually, suggest considerations for a sustainable future.

——–

The growth of national economies all over the world is still very uncertain due to geopolitical conflicts (e.g. Middle East, North Africa, Russia and Ukraine), rising US interest rates, oil price volatility, and the Eurozone crisis (World Travel Market, 2015a; Mackinson, 2011). Furthermore, the global pandemic has put even greater pressure on those national economies that rely most on international tourism. Nevertheless, travel is globally a growing market and in some countries remains the driver of many local economic systems (World Travel Market, 2015b). Places are today, more than ever, in competition with each other (Kerr, 2006) and therefore, they are all equally eager to promote their unique characteristics in order to sustain competitive advantages. It is critical to the survival of tourist destinations (and local economies) to be able to articulate their unique personalities and present them to customers (Kumar & Nayak, 2014).

Traditionally this task has always been the realm of place marketing, a discipline that for a long time has been understood as simply the application of marketing techniques to geographical locations (Eshuis et al., 2013) with the recognition that a place exists within a competitive market (Dhamija et al., 2011). However, a new approach has been growing within the practice, called participatory place branding (Holt, 2004). This approach is based on the assumption that a place narrative created in partnership with the local community is more appealing and ethical than one that is created from the top down, as locals provide a more well-articulated view of a destination. Participatory place branding has been deemed revolutionary in the discipline, to the point that Aitken and Campelo (2001) have even argued that community co-creation is the ‘holy grail of destination branding’.

Research Rationale

The travel and tourism industry is becoming more and more competitive, and in the future all tourist destinations will have to invest more energy and resources into articulating and promoting their unique characteristics (Mackinson, 2011). Tourists today have a different attitude towards travel than they did in the past. They are more educated, better informed, and have easy access to more destinations; they are also concerned with environmental issues and willing to participate in the life of communities they visit (World Travel Market, 2015b). However, money is often an issue and tourists today are always looking for the best price-for-value deal. They are not interested in ‘ticking boxes’ when travelling, but are attracted by unique, genuine, and authentic experiences (World Travel Market, 2015a).

In the face of these changes in the tourism industry across the world, new place marketing processes are essential in order to market to future tourist generations (Mackinson, 2011). The proposed research aims to join the debate on new place marketing processes, supporting the idea that participatory branding has the potential to be the ‘holy grail of place marketing’ (Aitken & Campelo, 2011). This study argues that co-creation of a place brand with the local community can be the first winning step towards gaining a competitive advantage over other destinations, particularly when marketing destinations off the mainstream tourism circuit. The proposed study is theoretically anchored to the body of academic research that supports the idea that ‘locals’ are an important dimension of place marketing and are necessary to the creation of a strong and successful place brand (Lichrou et al., 2014; Aitken & Campelo, 2011; Ashworth & Voogd, 1990; Kotler et al., 1999; Hall, 2000; Gunderson & Watson, 2007). Such studies promote the idea that in order to achieve sustainable tourism development, marketers must take into account the narratives of the people living in a place. This argument is based both on the ethical belief that ‘place products’ do not exist solely to accommodate the customers’ needs but are also home for a community, and the notion that local narratives are what really construct place meanings. ‘Sense of place’ is the core of place identity, and therefore the main focus of a place branding process should consider the body of notions, stories, and emotions generated by residents.

Methodology

The main aim of this research was the generation of different place experiences and narratives by the community that gravitates around Jerash. Based on Czarniawska’s argument (2004) that interviews can be treated as a means of narrative production, 23 phenomenological face-to-face interviews were carried out with local residents. In judging the optimum number of interviews, we followed the recommendation set out in Hanna & Rowley’s study (2013) that interviews of between 5 to 25 individuals who have experienced a phenomenon are sufficient, provided they are long interviews. Interviews were face-to-face as the direct contact between the interviewer and the interviewee is known to favor the production of a genuine narrative (Czarniawska, 2004).

In order to be interviewed, the individuals’ experiences had to be influenced by their involvement in diverse sectors in the area (Lichrou et al., 2014).

The style of the interviews followed the pattern of a conversation in order to facilitate the production of narratives, as theorized by Kvale (1996) and in light of Bruner’s (2004) definition of narratives as the main form through which people structure their experiences.

Interviews were videotaped in agreement with the interviewees.

In order to ensure a minimum level of consistency, the interviewer followed a series of open-ended questions such as:

– Are you originally from Jerash?

– When was the first time you visited the site?

– How often do you visit the site?

– What is the best part of the site?

– What is the worst part of the site?

– What is missing from Jerash?

– Do you think the site contributes to the city economy?

– Are you interested in interacting with tourists?

Following Lichrou et al. (2014) and Lieblich et al. (1998) use of narrative analysis framework, each interview was analyzed individually. As suggested by those authors, both a holistic-content approach and a categorical-content approach to the analysis were used. The first approach uses each entire narrative and its content, focusing on the meanings that the narrator intended to convey. Such an approach allowed for the identification of the key themes of each story within its original context. Recurring instances were color coded with the aim to reduce a large number of words and phrases to a set number of emergent themes that could be cross-referenced among the different interviews (Wilkinson, 2004), in line with the categorical-content approach to qualitative analysis.

The combination of these two approaches facilitated the identification of the themes across the different stories, without losing the context within which each theme arose.

The interviews were carried out both in English and Arabic in order to ensure accuracy and avoid misunderstandings. From these two, interviewees were given a choice of their preferred language. The interviewer was an English speaker and was supported during the process by an Arabic speaker for real-time translations which were double-checked at a later stage.

Findings

A total of 23 phenomenological interviews were collected within a span of two months during September and October of 2019. The goal was to ensure a representation of the local social reality; therefore, respondents were selected based on their association with a group of interests as seen in Table 1.

Below is the list of the ‘types’ of people interviewed from the diverse community gravitating around the archaeological site of Jerash:

| # | Group of interest | Name | Gender | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local authorities (Mayor) | Ali Qawqazah | Male | Over 40 |

| 2 | Council employee | Ali Shoka | Male | Over 40 |

| 3 | Foreigner living in Jerash (refugee or other) | Zena Umm Mali | Female | Over 60 |

| 4 | Jerash site management | Ziad Ghnimat | Male | Over 40 |

| 5 | Jerash site conservator | Firas Tbayshat | Male | Over 40 |

| 6 | Jerash site employee | Anal al-Momani | Female | Under 40 |

| 7 | Tourist agency or trip organizer | Munir Nassar | Male | Over 60 |

| 8 | Tourist guide | Youssouf | Male | Over 40 |

| 9 | Tourism trade (hoteliers’ union, restaurants) | Naser al Atoum | Male | Over 40 |

| 10 | Trade (businesses not directly related to tourism) | Omar | Male | Over 40 |

| 11 | Agricultural sector | Mamoun Hawanden | Male | Over 40 |

| 12 | Media & Press | Fayz Adibal | Male | Over 40 |

| 13a | Jerash resident – underaged kid | Runjay | Female | Underaged |

| 13b | Jerash resident – underaged kid | Sarah Dalel | Female | Underaged |

| 13c | Jerash resident – underaged kid | Salsabel Dalel | Female | Underaged |

| 13d | Jerash resident – underaged kid | Doha Dalel | Female | Underaged |

| 14 | Jerash resident – male adult | Nabil | Male | 21 yrs |

| 15 | Jerash resident – female adult | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 16 | Jerash resident – male/female senior | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 17 | Resident from a nearby town | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 18 | Amman and/or Irbid resident | Israa Thiab | Female | Under 40 |

| 19 | Military – Tourist Police | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 20 | Academic/researcher from the heritage field | Ina Kehrberg | Female | Over 40 |

| 21 | Ministry of Education local representatives | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 22 | Local teacher | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 23 | Religious local authority | Faisal Atma Abu Suleiman | Male | Over 40 |

| 24 | Intra site entertainment | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 25 | Organizers of the Jerash Festival | Ayman Samawi | Male | Over 40 |

| 26 | Culture, nature, social development etc. related NGO’s | Eman Owens Haddad | Female | Over 40 |

| 27 | Site goods seller | Adam Ateh | Male | Under 40 |

Table 1 – Profile of the locals interviewed at November 2nd, 2019

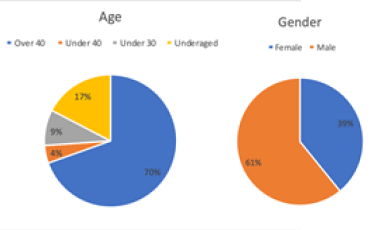

A little over 60% of respondents were male and belonging to the “over 40” age group. Each interview lasted from a minimum of 15 minutes to a maximum of 1 hour. Each interview was recorded, and key words, expressions, and concepts were transcribed, following the holistic-content approach (Lieblich et al., 1998).

Subsequently, similar concepts were grouped following the categorical-content approach (Lieblich et al., 1998), with the aim of outlining macro-categories. At a later stage, categories were cross-referenced and color-coded to highlight recurring themes.

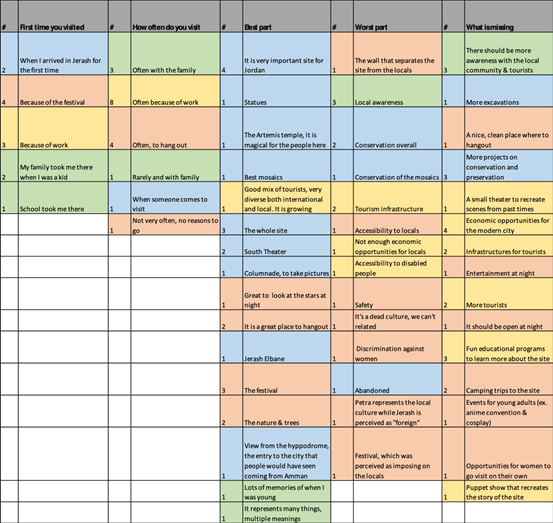

As shown in Table 2, each question asked is represented by a column. Macro categories are listed under each question with the number of occurrences among all participants. Such an approach was deemed applicable only for 5 out of 8 questions asked of the locals.

The analysis of the interviews brought up multiple meanings and narratives, and the colours refer to recurring themes, which were expressed by the author as follows:

– Blue – Pride and Beauty

– Orange – The Main Square

– Green – The Old Home

– Yellow – The Resource

Recurring themes were then articulated in four different narratives.

Blue – Pride and Beauty

Jerash is the destination, a beautiful and important symbol of Jordan. This is the narrative of those who started to call Jerash ‘home’ later in life and those who have a ‘foreign outlook”’

The archaeological site is the place locals feel proudest of and where they would start a tour of the whole city. With its beautiful mosaics, colonnades, and statues, it is the most impressive gate to the modern city. For these reasons, this narrative is most concerned with the conservation of the site and therefore with all the operations that should take place in the archaeological site in terms of restorations. Locals feel their pride for the site is not shared by the local administration or those who are generally charged with its care, leaving them feeling anxious about the future of the archaeological area.

Orange – The Main Square

The archaeological site of Jerash is much more than cultural heritage; it is also the only nice place where the community can relax, hang out, enjoy nature and simply spend their spare time with friends and family. This narrative reflects the lack of spare time activities in the village and the need for locals to have a safe and nice place to meet. In this narrative, locals explore the lack of accessibility of the archaeological site — both cultural and physical. In terms of physical barriers, locals are concerned with the fact that the archaeological site is perceived as physically ‘detached’ and ‘alien’ from the modern town. From a cultural perspective, they would like to ‘know more’ about its history in a ‘fun and entertaining way’. They see it as the focal point of the Jerash experience, where people exchange stories among the community and with the tourists who would become part of an enlarged temporary community. Even if stands in stark contrast to the typical use of the site, the Jerash Festival for Culture and Arts is a key asset of this narrative

Green – The Old Home

Jerash is the place of life, the home, and the family. Nice people and different communities inhabit its village, and the archaeological site is the recurring background in many families’ memories. It is the place where you would take your loved ones for a family picture, the recurring symbol of school trips and history lectures. The archaeological site of Jerash is part of the history of the place, it is familiar and reassuring. Walking down the ancient roads is just like taking a trip down memory lane.

It is not a dynamic location and as time passes, ancient Jerash’s sense of place becomes dusty, its narrative confused and non-linear. Locals are clearly connected to the site at a deeper emotional level; however, they don’t seem able to articulate the reason behind this connection. It is like an extension of their being, like a limb: it has always been there, and supposedly always will be.

Yellow – The Resource

The archaeological site of Jerash is perceived as a potentially strong economic driver for the local economy. Jerash is in fact also a place of work, a space where money can be made and the reason why tourists are willing to visit the area and generate income for the modern town. However, there is a clear disparity between the perceived value of the site and the actual value it currently is able to generate for the Jerash community. This narrative is mostly concerned with finding reasons and solutions to the scarcity of job opportunities in Jerash. Tourism is looked at as the main economic asset; however, there emerges a sense of confusion around how it should be enabled and its actual contribution. Overall, there is a sense of insecurity and frustration around the matter which turns the locals towards the local administration and the government, who are looked at as the guides who should provide direction and support to the regeneration of the area.

Table 2 – Concepts and categories emerged from the interviews are cross-reference

and color-coded to highlight recurring themes

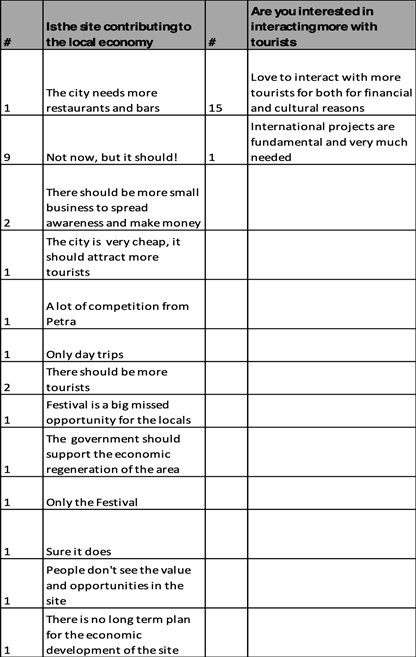

The final two questions of the interviews (‘Do you think the site contributes to the city economy?’ and ‘Are you interested in interacting with tourists?’ respectively) were analysed separately from the previous ones but could be incorporated into the last narrative. These questions are in fact mostly concerned with the binomial ‘tourism & economy’ and reflect community concerns regarding potential economic regeneration of the area through tourism. Overall, interviewees were extremely on-point in recognizing the assets and shortcomings of the city against the competitors of Petra and Amman. Equally, they showed an incredible willingness and interest in interacting with foreigners, who are perceived as a huge opportunity. Further, this is true not only from an economic perspective but also from a cultural one: as a matter of fact, most locals see interacting with tourists as an opportunity to ‘grow’ as individuals, learn more about the world, and even better their education and use of the English language. Once again though, the community seems to lack the financial and cultural tools to put this vision into practice and look to the local authorities as the natural enablers of the process.

Table 3 – Focus on tourism and economy in Jerash

Discussion

The narratives co-created with the locals captured multiple meanings of the archaeological site of Jerash.

In Blue – Pride and Beauty participants draw attention to the aesthetic appreciation of the place. Here the place is understood as a pictorial representation of the surroundings, a view that finds reference in Urry’s definition of the tourist experience as the ‘tourist gaze’ (1990). As theorized by Urry, the ‘tourist gaze’ is what tourists expect from a place or tourist destination. The ‘gaze’ is a stereotypical image of a place, which is the result of marketing, media, and local authorities’ efforts to promote a destination. Locals generally perceive this set of expectations and try to reflect this ‘gaze’, mostly for financial benefit. This narrative acknowledges the archaeological site through the visual recognition of the area as a product to be created, maintained, and consumed only aesthetically.

In Yellow – The Resource locals highlight the entrepreneurial identity of the territory. The archaeological area becomes a commercial tool and participants are engaged in the activities of promoting tourism and its related economy. Similar to what was observed in Lichrou’s case study of Santorini (2014), locals of Jerash seem to perceive tourist hospitality and overall management of the site for tourism purposes as their main commercial activity. This narrative recognizes tourism as a sustainable form of economic development and regeneration for the area.

The narrative Green – The Old Home, instead, refers to the sense of belonging to the place and the emotional attachment that the locals have to the archaeological site. Such images are the result of the interaction between emotional attachment and life memories. Locals recognise their experience of the place as a value, an asset, and something potentially desirable for tourists. Specifically, interviewees talked about the aspects that characterise this narrative as something that has been long overlooked and is out of touch with respect to the ‘outside world’.

This sense of detachment from what the area currently offers tourists is something that also emerges in the last narrative, Orange – The Main Square. Jerash does not have a tradition as a tourist destination, but locals seem to have a precise idea of the features that could potentially attract visitors to the area, if properly developed.

The images drawn from the interviews embrace culture, society, economics, and politics. What appears clear from these narratives is that a sense of place is a mix of ‘extraordinary and every day, negotiated through the experiences of living in and making a living in a place’ — as theorized by Lichrou et al. (2014, p. 848) –- which has huge implications on how a place is marketed. They reveal ‘different forms of local subjectivity’ (Lichrou et al., 2014, p.850), which contribute to the relationship between place, identity, and local population, key features of sense of place and therefore of the place branding strategy.

Limitations

In-depth interviews were carried out in the form of a responsive interview (Rubin & Rubin, 2012), meaning that the researcher reacted to what the interviewee was saying and asked further questions to avoid misunderstanding and to capture meanings in relation to the context of the conversation.

Following Foddy’s (1994) definition of reliability in relation to interviews and questionnaires as to when questions are understood by respondents and answers are understood by the researcher in the way they want the other person to understand, such interviews can be considered reliable. In regards to sampling, however, even though individuals were selected in a way to ensure a representation of the Jerash social reality, individuals were chosen among a pool of connections made by the interviewers in past years, and when direct connections were not available the interviewers relied on referrals (snowball sampling). This brings an intrinsic affective bias that limits the validity of this research (Collins & Hussey, 2003). On top of that, an interviewee could not be found for all of the identified categories, which is another limit of this research in terms of representativeness of the local community.

Managerial Implications

Even though results from this study present some limitations, this research has direct managerial implications for the bodies that will and are managing the archaeological site for tourism purposes.

First of all, it proved that locals have a very rounded view of the archaeological site of Jerash; they are able to articulate it in an attractive way; and they seem to understand what would attract visitors.

It also appears clear from the in-depth interviews with the locals that they feel the promotion of the area as a tourist destination has not been professionally articulated so far. Even though Jerash does welcome numerous tourists during the year, locals still perceive it as being at a very early stage of its development. All narratives agree that the main assets of the area are the ‘wow effect’ of the archaeological site and the opportunity to be part of an ‘enlarged temporary community’ sharing in the emotional bond locals have with the place.

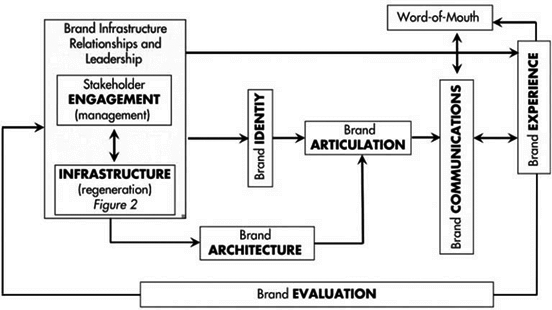

What emerges from this study is that local narratives are an asset for place branding for many reasons. Once leadership understands and negotiates place-brand architecture with the owners (stakeholders) of a place, brand articulation will reflect the evolving reality of the place whilst maintaining alignment with a constantly changing market and also strengthening stakeholder relationships. Such an approach theoretically ‘ticks all the boxes’ for a successful place marketing strategy, a sustainable competitive advantage, and local economic development.

More specifically, it is recommended that management of the archaeological area engages proactively in a discussion with the locals on the identity of the area as a tourist destination; considers the potential positive influences of local narratives on the brand equity of area; and examines the constraints of a univocal, top-down, corporate narrative. Leadership of the town should guide the creation and evolution of a new brand identity, beginning with building a collaborative relationship with a range of stakeholders (locals, local authorities, regional authorities, businesses, tourists, foreigners residing in the area) to ensure a coherent and relevant place-branding identity which takes into account the different layers of Jerash and leverages its multifaceted character. Following the Strategic Place Brand Management (SPBM) model by Hanna & Rowley (2013), this new identity and architecture should be articulated coherently in a place-branding document and shared with those who collaborate on the project, then communicated consistently through all outputs available to the company. Leadership should also make sure place branding is reflected by the branding experience, confirming the services actually offered to tourists. Finally, management of the archaeological area should set up an evaluation system in order to adjust the narrative to both local and market changes and keep the brand relevant over the years.

Bibliography

Bruner, J., 2004. Life as narrative. Social Research: An International Quaterly, 71 (3), 691-710.

Collins, J. & Hussey, R., 2003. Business Research: A Practical Guide for Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Czarniawska, B., 2004. Narratives in Social Science Research. New York: Sage Publications.

Foddy, W., 1994. Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hanna, S. & Rowley, J., 2008. An analysis of terminology use in place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4 (1), 61-75.

Hanna, S. & Rowley, J., 2013. A practitioner-led strategic place brand-management model. Journal of Marketing Management, 29 (15-16),1782-1815.

Kvale, S., 1996. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. New York: Sage Publications.

Lichrou, M., O’Malley, L. & Patterson, M., 2014. On the marketing implications of place narratives. Journal of Marketing Management, 30 (9-10), 832-56.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R. & Zilber, T., 1998. Narrative Research: Reading Analysis and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rubin, J.H. & Rubin, I.S., 2012. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Wilkinson, S., 2004. Focus group research. In D. Silverman, ed. Qualitative research: Theory, method, and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 177–199.

***

You can watch all the interviews done in Jerash by Chris Boyd on the project’s

Countries